Pharmaceuticals find more than one solution in ethanol

MAY 26, 2022 | ISOLVENTS CHEMICALS

Abstract

Ethanol is a reliable compound for its use as a solvent. In this article we explore the potential growth the pharmaceutical sector could experience, considering the good ethanol has done for fuel industries. Comparing and contrasting Malawi and Kenya that value ethanol in their energy sectors at different levels, it becomes notable that ethanol remains a commodity worthy of higher production and distribution rate. Yielding international ethanol markets to this end would prove beneficial in many ways, especially the pharmaceutical industry in countries like Malawi that have a greater need for better general health care. The health care in other sub-Saharan African countries could be positively impacted in a direct manner by importation of ethanol from countries like South Africa, leading the rest of Africa to reap the benefit of high quality ethanol use.

Ethanol is a simple organic molecule found in nature. A hydrocarbon constituted of its bases, carbon, hydrogen, and a hydroxide group introducing oxygen. These three elements are found readily in organic material, yet bound together in a specific conformation as ethanol, bringing us a compound set apart as a multifunctional resource.

To only list a few applications explored in Africa: biofuel, solvent, detergent, and antiseptic – proves its significance as a commodity in our day. Usually, the value of a compound is closely linked to its availability. If it’s rare, it’s valuable. But not so with ethanol. It remains a valuable stock in the market despite its abundance. Some African countries are on the cusp of introducing ethanol as a motor-fuel, showing that it’s no longer considered a luxury good traced at low concentrations in bottles of drink.

Economic perspectives from Malawi and Kenya

To get a lay of the ethanol economy in Sub Saharan Africa we’ll look at Malawi and Kenya, each offering unique insight on how ethanol trade effects various industries, specifically the pharmaceutical industry. The production of ethanol in Malawi and Kenya is founded on the agricultural sector with sugarcane being the feedstock to make ethanol.

Malawi has two sugar production sites in Dwangwa and Nchalo which together sustain some parts of the country’s energy sectors. Having fully integrated biofuels into their energy system with some of the fuel blended with 20% ethanol. Any ethanol that is domestically produced is syphoned to motor-fuel blending, paying great dividends to the transport sector, but hamstringing other industries such as the pharmaceutical industry. EthCo is a distillation company in Nchalo that entered the pharmaceutical market with their ethanol, but it cannot be sustained with the growing demand for ethanol fuel.

Sugarcane is the highest yield in agriculture for Kenya – which has lent itself well to an established ethanol trade. 56 million litres of ethanol is produced annually in western Kenya in the province of Nyanza. Of this, a significant proportion is dedicated to pharmaceuticals. Kenya is one of the leading countries in Africa with the 5th highest import and export rate of pharmaceuticals. The standard ethanol pathway when traced in its economy from sugar to products, arrives in one of three areas: blended fuels, breweries, and medicine. In the latter category of medicine, anhydrous ethanol is denatured and used as a solvent in pharmaceuticals.

Having briefly considered the economies of Malawi and Kenya, what is most noteworthy are inextricable links between ethanol production, the sugar value chain and the pharmaceutical industry. This stays true when contrasting the two countries and finding their predicaments to be different. Whether or not the pharmaceutical industry is comparatively weak, any country will benefit from a growing ethanol economy.

Foreign exchange

A straight-forward and convincing method in boosting domestic ethanol production in Sub Saharan Africa is to create a supply and demand in the market. Countries have a lot of capital designated for the manufacture of ethanol, which can bring about a supply and demand in others that have comparatively less capital.

In South Africa, where we have a high ethanol output at our fingertips, we can serve other countries by entering and promoting international trade. As large as an undertaking this seems to be, the only task at hand is to bolster the selling power of ethanol by offering it at a premium that makes it affordable and beneficial to foreign economies.

A working example of this is Kenya’s situation in foreign exchange. In 2004 a drought so devastating, blighted the land that food aid was required, and sugar production temporarily reduced. But their foreign exchange policies brought them through that time and in 2018 their spike in gross domestic product was attributed to the rise of small businesses that diversified their economy and strengthened their foreign exchange. Now they have developed self-sufficiency in the industry of pharmaceuticals with surpluses being exported to neighbouring countries.

It is a winsome prospect to invest with a government that is generally friendly and have enacted several regulatory reforms to simplify foreign exchange.

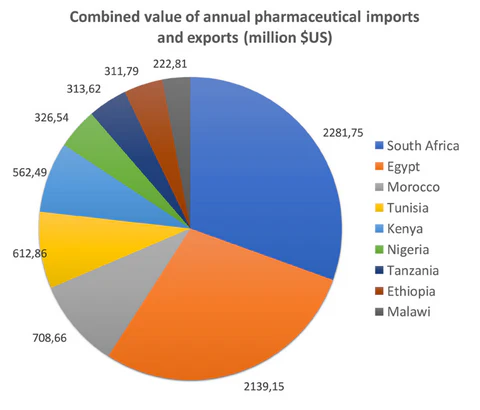

Kenya could be a model for Malawi, leading them to the same success. Consider the pie chart and compare the activity of international pharmaceutical trade. Currently Malawi imports pharmaceuticals at half the quantity to that of Kenya, despite their low value of ethanol trade.

Supplying them with ethanol and injecting their economy with this resource has potential. It will provide a greater flow of ethanol stock conversion to pharmaceuticals. This could eventually lead Malawi to produce enough pharmaceuticals of their own, reducing importation and making better use of ethanol stock.

Why pharmaceuticals

Most African countries are in the same position as Malawi, sharing a great need for growth in capacity of their pharmaceutical industry. This is most acutely felt when asking the age-old question: why can’t Africa manufacture the medicines it needs?

To improve public health on the largest continent, the domestic procurement of medical products is essential. Which is why strategies of establishment of pharmaceutical industries should be considered at every turn. This is where we find ourselves with the service we can provide as distributors of ethanol.

Ethanol availability is necessary since its used as a solvent in most pharmaceutical products. Because of its low melting point and high polarity, it’s a suitable medium for most compounds that need to be kept in solution with the aim of interacting with our physiology.

It dissolves active ingredients and keeps them in liquid form below freezing temperatures, extending their lifetime, and allowing ease of storage.

Further reasons for ethanol being a worthy ingredient in pharmacy is its antiseptic, sedative, and cooling properties. This makes it a suitable solvent for topical wound dressing, oral or intravenous administration.

Knowing that better health care can be a reality for African countries by virtue of a stronger ethanol economy in Sub Saharan Africa. We at iSolvents are committed to supporting countries like Malawi through ethanol trade.

Our ethanol range includes mixtures at different concentrations, up to 99,9% purity. We also offer denatured ethanol for its suitable for use in pharmacy as solvent or rubbing alcohol.